Algorithm of Thought

The Right to Disagree

Contrary to popular belief, you can't just disagree with someone because you feel like it. You have to __earn__ the right to disagree with someone's position.

Contrary to popular belief, you can't just disagree with someone because you feel like it. Disagreement is not a fundamental human right (although it certainly seems to be a fundamental human condition) - you have to earn the right to disagree with someone's position.

How do you earn the right to disagree?

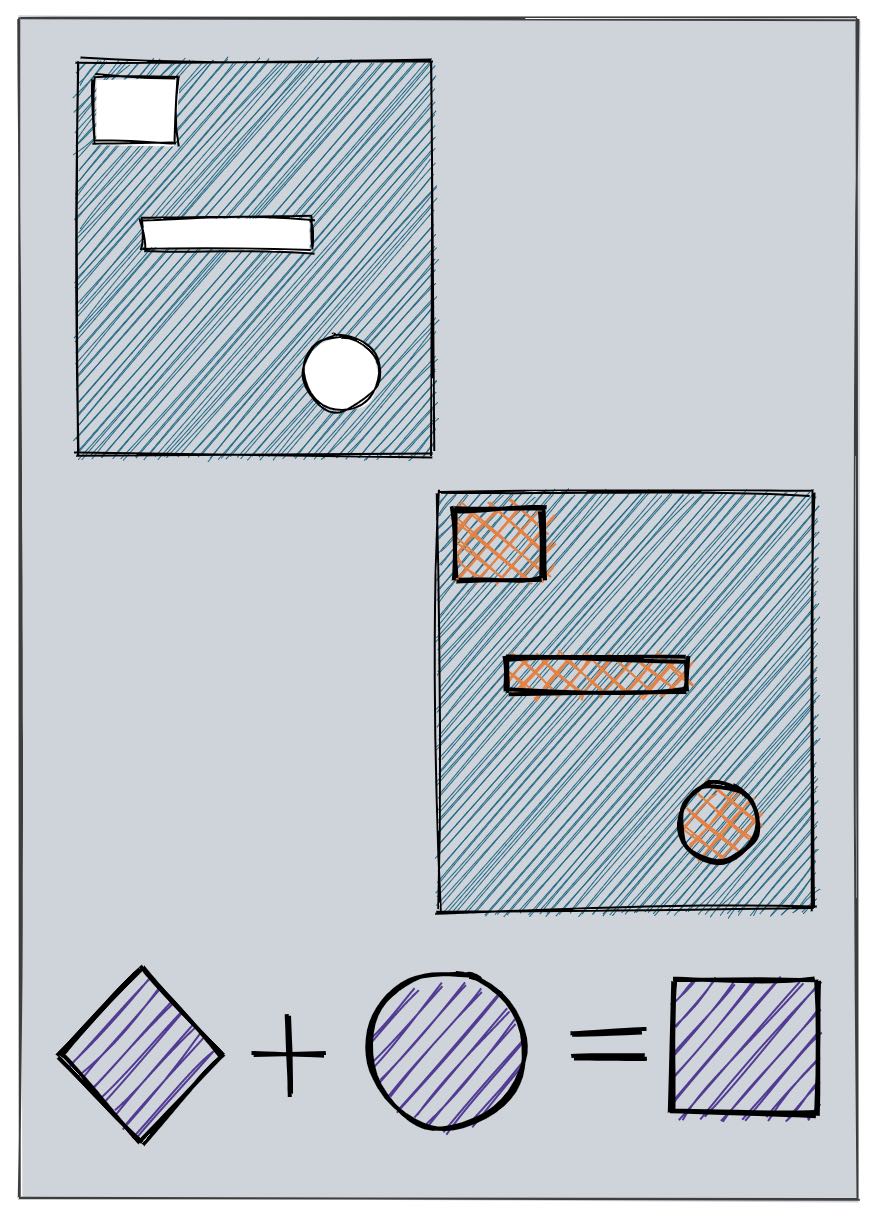

In "How to Read a Book" Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren share a great algorithm of thought to figure out whether you're allowed to disagree with a position or not and what exactly your disagreement is.

The first step of course is understanding the argument being made, and understanding it deeply. Once you've done that, there are three (~four) reasons to disagree with a position.

If you can't fit your disagreement in one of these slots you are not allowed to disagree. It's rather simple, really.

So what are the reasons?

Reasons to Disagree

- Missing information: if the analysis as presented is missing crucial information that if the author had known it would have altered their analysis - that's a reason to disagree with them.

- Wrong information: if the analysis rests on a piece of information that is simply wrong, you are allowed to disagree.

- Reasoning error: if all relevant facts are included and reported correctly, there's only one reason left to disagree, which is logical errors. There's many of them, but Adler & Van Doren give what I agree are the most common ones: non-sequiturs and inconsistencies. A non-sequitur is when you say "1 + 1 is 2 and that's why the sun rises in the East" - one does not follow from the other. Inconsistencies is when the argument claims two things that aren't compatible logically: "The sun rises in the East" and "The sun settles in the North" are (on our planet) logically inconsistent.

If you disagree with someone, your criticism has to include one of these three components. If you can't fit it in these three categories, you should go back to the argument and figure out where you don't understand it. If you can't find anything, you have to agree.

There's one other thing you might say that's disagreement-adjacent, and that is that the analysis is incomplete. To quote directly, Adler & Van Doren say that arguing an analysis is incomplete means that the author has

"not solved all the problems [they] started with, or that [they have] not made as good a use of [their] materials as possible, that [they] did not see all their implications and ramifications, or that [they have] failed to make distinctions that are relevant to [their] undertaking. It is not enough to say that a book is incomplete. Anyone can say that of any book."

Adler & Van Doren also point out:

"This fourth point is strictly not a basis for disagreement. It is critically adverse only to the extent that it marks the limitations of the author’s achievement. A reader who agrees with a book in part—because he finds no reason to make any of the other points of adverse criticism—may, nevertheless, suspend judgment on the whole, in the light of this fourth point about the book’s incompleteness."

The question now is how to make sure to figure out consistently what reasons for disagreement you have - if you have any. I suggest using this template in your note-taking tool of choice:

- Missing information?

- Wrong information?

- Reasoning Errors?

- Non Sequitur?

- Inconsistency?

- Incomplete Analysis?

Every time you read a source, or come to the end of an argument you're encountering somewhere, paste these questions in and help them sort your thinking. Once you've worked through them you're ready to formulate your position - if there's nothing under these prompts: awesome, you read a book you agree with! If you're unhappy it might mean that you don't like the argument, but you can't disagree. If there's lots to write under these questions: great, time to sharpen your thinking and write down your position in detail. You've earned your right to disagree!

Related Topics

Join the Cortex Futura Newsletter

Subscribe below to receive free weekly emails with my best new content, or follow me on Twitter or YouTube.

Join and receive my best ideas on algorithms of thought, decision making, and Roam Research